Clearing Up Mahogany Mixups - The Lowdown

by Eric Meier of The Wood Database

I remember in my (slightly) younger days, stepping into a big box hardware store and picking up some shrink-wrapped boards labeled “mahogany” with prices that seemed just too good to be true. I told the employee that they had very good prices on mahogany, and he half-smirked and hesitantly commented “well, there’s a lot of different types of mahogany out there…” So began my early lessons in this sometimes-coveted and sometimes-disdained wood. Little did I know that these discrepancies stemmed from the woodworking equivalent of comparing apples to oranges.

UN-JUMBLING THE MAHOGANY MESS

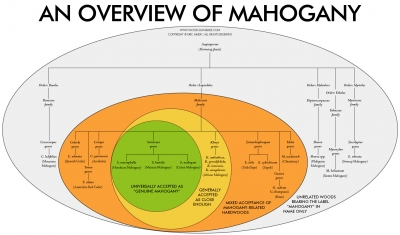

Hypothetical situation: So you’ve just stumbled across some sort of “mahogany” wood, and you’re wondering if you have the real deal. After all, there are currently over a half dozen types of mahogany listed on The Wood Database. Much like cedar, the “mahogany” label gets tossed around with relative liberality—and not always with regard to the botanical designation of the wood in question. Ultimately, the ambiguous term mahogany remains somewhat subjective. But regardless of where anyone happens to draw the line on what is and is not true mahogany, certain facts and scientific classifications of the trees remain constant, and a general consensus can at least be made on the objective facts surrounding these woods.

But before we sort everything out, it would be helpful to ask a needed question: why bother trying to sort things out? If it looks like mahogany, what’s the difference anyhow? A lot, it turns out. Beyond simply being worth more in terms of dollars per board-foot, there are practical implications to using true mahogany. Listed below are the ideal characteristics (hopefully) found in the wood: chances are most non-mahoganies will lack at least one (or more) of these characteristics.